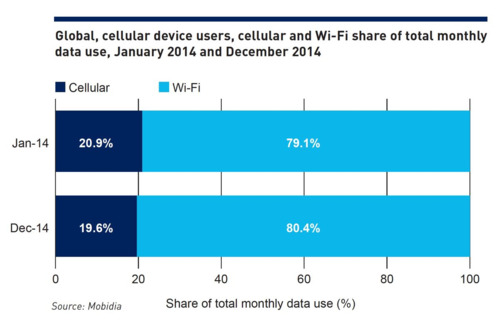

The LTE small cell market has generated a great deal of interest from MNOs and RAN vendors over the past few years. The goals of this effort are to greatly increase cellular capacity in high traffic locations and to improve indoor coverage. The primary applications will be packet voice and other real-time applications, along with high value data traffic. However, the bulk of the data traffic in high-density locations will continue to be handled by Wi-Fi (check out the chart below).

Industry pundits have forecasted rapid growth in LTE small cell deployments, but that growth has been slow to materialize. In some cases there were technical problems that needed resolution, like interference mitigation with the macro cellular layer, but the real challenges are around the business model. At the heart of the business model discussion is the issue of “who pays” to deploy the network. With macro cellular deployments, the operator always pays, but with small cell deployments in hotels, shopping malls, hospitals, and schools the burden starts to shift, for the most part, to the venue.

The LTE small cell market has generated a great deal of interest from MNOs and RAN vendors over the past few years. The goals of this effort are to greatly increase cellular capacity in high traffic locations and to improve indoor coverage. The primary applications will be packet voice and other real-time applications, along with high value data traffic. However, the bulk of the data traffic in high-density locations will continue to be handled by Wi-Fi (check out the chart below).

Industry pundits have forecasted rapid growth in LTE small cell deployments, but that growth has been slow to materialize. In some cases there were technical problems that needed resolution, like interference mitigation with the macro cellular layer, but the real challenges are around the business model. At the heart of the business model discussion is the issue of “who pays” to deploy the network. With macro cellular deployments, the operator always pays, but with small cell deployments in hotels, shopping malls, hospitals, and schools the burden starts to shift, for the most part, to the venue.

In many ways, the enterprise LTE small cell market is much more like Wi-Fi than it is like the outdoor macro cellular market. With Wi-Fi the venue almost always pays, the network can be installed by a VAR (value added reseller), and the equipment is inexpensive and easy to operate. This is the trifecta for a successful enterprise deployment.

Looking at the LTE small cell opportunity it is important to focus on the indoor opportunity, as that is where most data traffic is consumed, and that is where cellular services will sometimes have coverage issues. When looking at indoor wireless services there are two technologies that have been very successful and they are DAS and Wi-Fi. DAS (distributed antenna systems) are generally deployed in high-density locations that are over a few hundred thousand square feet.

These include stadiums, airports, convention centers, and the like. The high cost of DAS deployments has limited them to these very large, heavily utilized locations. The primary use for DAS is in providing good voice coverage in these large venues, while Wi-Fi networks handle the heavy data load. Both technologies have a big advantage when it comes to deploying indoors and that is neutral host support. Large venues will not typically allow a radio technology into their building unless it can support ALL users at that venue. Any other arrangement isn’t to their benefit. DAS systems are usually deployed by neutral host service providers, which resell access to the major MNOs. If the venue is desirable enough (airports and convention centers) the neutral host service provider also pays a hefty site rental fee to the venue.

Wi-Fi networks are also neutral host and are typically installed by the venue to provide data services in their facility. This is an area where Ruckus has been very successful. In some cases the venue owns the network and in other cases they purchase a managed service.

Say Hello to Small Cells

The purpose of LTE small cells is to provide enhanced cellular services in venues of all types. In really large venues (those suitable for DAS) the mobile operator is more than willing to pay for the small cell deployment along with any site rental fees. These are high-capacity venues that attract tens of thousands, or even hundreds of thousands of people per day. When going to smaller venues, the subject of who pays for the small cell gets a lot more complicated. In some cases the MNO might pay, but more often than not the venue has to pay. There just isn’t enough traffic to justify the expense for the operator and they will fall back on the outside-in approach to cellular coverage. For some buildings and in some locations, the outside-in approach just doesn’t do the job.

In many ways, the enterprise LTE small cell market is much more like Wi-Fi than it is like the outdoor macro cellular market. With Wi-Fi the venue almost always pays, the network can be installed by a VAR (value added reseller), and the equipment is inexpensive and easy to operate. This is the trifecta for a successful enterprise deployment.

Looking at the LTE small cell opportunity it is important to focus on the indoor opportunity, as that is where most data traffic is consumed, and that is where cellular services will sometimes have coverage issues. When looking at indoor wireless services there are two technologies that have been very successful and they are DAS and Wi-Fi. DAS (distributed antenna systems) are generally deployed in high-density locations that are over a few hundred thousand square feet.

These include stadiums, airports, convention centers, and the like. The high cost of DAS deployments has limited them to these very large, heavily utilized locations. The primary use for DAS is in providing good voice coverage in these large venues, while Wi-Fi networks handle the heavy data load. Both technologies have a big advantage when it comes to deploying indoors and that is neutral host support. Large venues will not typically allow a radio technology into their building unless it can support ALL users at that venue. Any other arrangement isn’t to their benefit. DAS systems are usually deployed by neutral host service providers, which resell access to the major MNOs. If the venue is desirable enough (airports and convention centers) the neutral host service provider also pays a hefty site rental fee to the venue.

Wi-Fi networks are also neutral host and are typically installed by the venue to provide data services in their facility. This is an area where Ruckus has been very successful. In some cases the venue owns the network and in other cases they purchase a managed service.

Say Hello to Small Cells

The purpose of LTE small cells is to provide enhanced cellular services in venues of all types. In really large venues (those suitable for DAS) the mobile operator is more than willing to pay for the small cell deployment along with any site rental fees. These are high-capacity venues that attract tens of thousands, or even hundreds of thousands of people per day. When going to smaller venues, the subject of who pays for the small cell gets a lot more complicated. In some cases the MNO might pay, but more often than not the venue has to pay. There just isn’t enough traffic to justify the expense for the operator and they will fall back on the outside-in approach to cellular coverage. For some buildings and in some locations, the outside-in approach just doesn’t do the job.

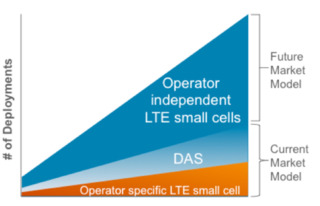

The figure on the left shows that to hit the “hockey stick” projections that many industry analysts have for LTE small cells a neutral host model is essential.

To get the venue to pay, the solution almost always has to be neutral host, especially in a Bring Your Own Device (BYOD) world. So how might an LTE small cell be neutral hosted? There are a couple of options that come to mind. It all starts with spectrum, and more to the point, whose spectrum.

1) National roaming is one way to solve this problem. With this approach the LTE small cell network is installed using spectrum of one of the national operators who then sets up roaming arrangements with all their competitors such that all their subscribers can now access the network. This gives the venue what they need which is an indoor cellular network that anyone can access. This is not a technical solution to the neutral host problem, but a business solution.

2) Another option is to again use the spectrum of one of the national operators, but instead of having to roam with the host operator, the small cell can support the PLMN IDs of the other MNOs who can then tunnel traffic back to their Evolved Packet Cores (EPC). This essentially creates a shared small cell in much the same way that a Wi-Fi access point can be shared using separate SSIDs (service set identifiers). This is better known as MOCN (multiple operator core network) and it does add a great deal of complexity, as the small cell ends up talking to multiple EPCs instead of just one.

3) A 3rd option is for a neutral host service provider (VAR, DAS vendor, tower company, etc.) to deploy the network using its own licensed spectrum. These neutral host service providers might also handle DAS deployments as well. So what spectrum might a neutral host service provider use to deploy a network and what does the business model look like? One obvious place to look is in the low power bands that are part of the FCC’s Citizens Broadband Radio Service (CBRS) at 3.5GHz.

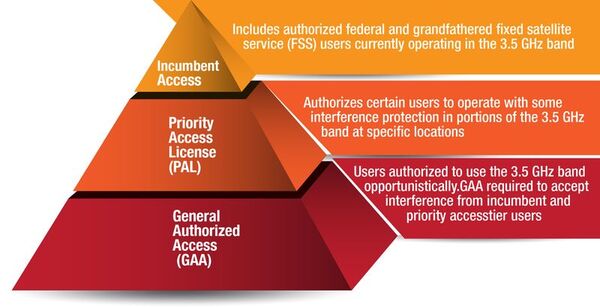

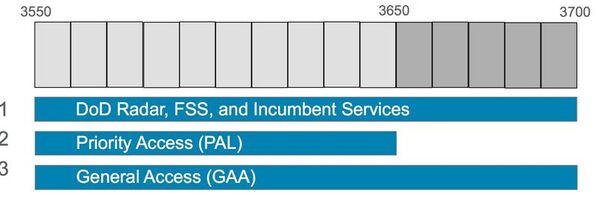

The FCC has done something very interesting with the 3.5 GHz band and we can only hope that other regulatory jurisdictions follow suit. The key elements here are a very unique approach to the sharing of spectrum where the incumbent user, in this case the U.S. Navy, has first rights to the spectrum. If they aren’t using it, then a business can get a Priority Access License (PAL) to operate a small cell network, and if there is no PAL user, or Navy user, it can be used for General Authorized Access (GAA), which usually means Wi-Fi. This hierarchy of license priorities is depicted in the following figure.

The figure on the left shows that to hit the “hockey stick” projections that many industry analysts have for LTE small cells a neutral host model is essential.

To get the venue to pay, the solution almost always has to be neutral host, especially in a Bring Your Own Device (BYOD) world. So how might an LTE small cell be neutral hosted? There are a couple of options that come to mind. It all starts with spectrum, and more to the point, whose spectrum.

1) National roaming is one way to solve this problem. With this approach the LTE small cell network is installed using spectrum of one of the national operators who then sets up roaming arrangements with all their competitors such that all their subscribers can now access the network. This gives the venue what they need which is an indoor cellular network that anyone can access. This is not a technical solution to the neutral host problem, but a business solution.

2) Another option is to again use the spectrum of one of the national operators, but instead of having to roam with the host operator, the small cell can support the PLMN IDs of the other MNOs who can then tunnel traffic back to their Evolved Packet Cores (EPC). This essentially creates a shared small cell in much the same way that a Wi-Fi access point can be shared using separate SSIDs (service set identifiers). This is better known as MOCN (multiple operator core network) and it does add a great deal of complexity, as the small cell ends up talking to multiple EPCs instead of just one.

3) A 3rd option is for a neutral host service provider (VAR, DAS vendor, tower company, etc.) to deploy the network using its own licensed spectrum. These neutral host service providers might also handle DAS deployments as well. So what spectrum might a neutral host service provider use to deploy a network and what does the business model look like? One obvious place to look is in the low power bands that are part of the FCC’s Citizens Broadband Radio Service (CBRS) at 3.5GHz.

The FCC has done something very interesting with the 3.5 GHz band and we can only hope that other regulatory jurisdictions follow suit. The key elements here are a very unique approach to the sharing of spectrum where the incumbent user, in this case the U.S. Navy, has first rights to the spectrum. If they aren’t using it, then a business can get a Priority Access License (PAL) to operate a small cell network, and if there is no PAL user, or Navy user, it can be used for General Authorized Access (GAA), which usually means Wi-Fi. This hierarchy of license priorities is depicted in the following figure.

This new 3.5 GHz spectrum allocation and management scheme is very interesting in that the coverage areas match census tracks, which match population density, and for which there are 74,000 in the U.S. The transmit power levels are also limited. In fact, they closely track Wi-Fi power levels of 24-30 dBm, which makes them ideal for small cell usage.

Basically anyone that controls real estate can operate a neutral host LTE small cell network using this spectrum management approach. These neutral host operators would roam with the major MNOs. They need not have any customers of their own and would strictly be acting as a visited network. The neutral host service providers would be paid by the venue to install and operate the network so as to provide greatly enhanced cellular service in that facility. The venue recovers this cost because a strong cellular service helps them to sell whatever it is that drives their business. It could be hotel rooms, hospital beds, tuition, etc.

The most fascinating aspect of the LTE small cell business is not in the technology but in the business models that will emerge to support and pay for this greatly enhanced cellular connectivity.

Talk about a ruckus!

This new 3.5 GHz spectrum allocation and management scheme is very interesting in that the coverage areas match census tracks, which match population density, and for which there are 74,000 in the U.S. The transmit power levels are also limited. In fact, they closely track Wi-Fi power levels of 24-30 dBm, which makes them ideal for small cell usage.

Basically anyone that controls real estate can operate a neutral host LTE small cell network using this spectrum management approach. These neutral host operators would roam with the major MNOs. They need not have any customers of their own and would strictly be acting as a visited network. The neutral host service providers would be paid by the venue to install and operate the network so as to provide greatly enhanced cellular service in that facility. The venue recovers this cost because a strong cellular service helps them to sell whatever it is that drives their business. It could be hotel rooms, hospital beds, tuition, etc.

The most fascinating aspect of the LTE small cell business is not in the technology but in the business models that will emerge to support and pay for this greatly enhanced cellular connectivity.

Talk about a ruckus!